The latest partnership between Pivot Bio and the Soil & Water Outcomes Fund (SWOF) will be dismissed by some as another sustainability press release. That would be a mistake. If the collaboration proves that farmers can be paid simultaneously for cleaner water and for reducing synthetic nitrogen—without tripping over claims accounting—the economics on a Midwestern acre change in ways that finance chiefs and utility commissioners cannot ignore.

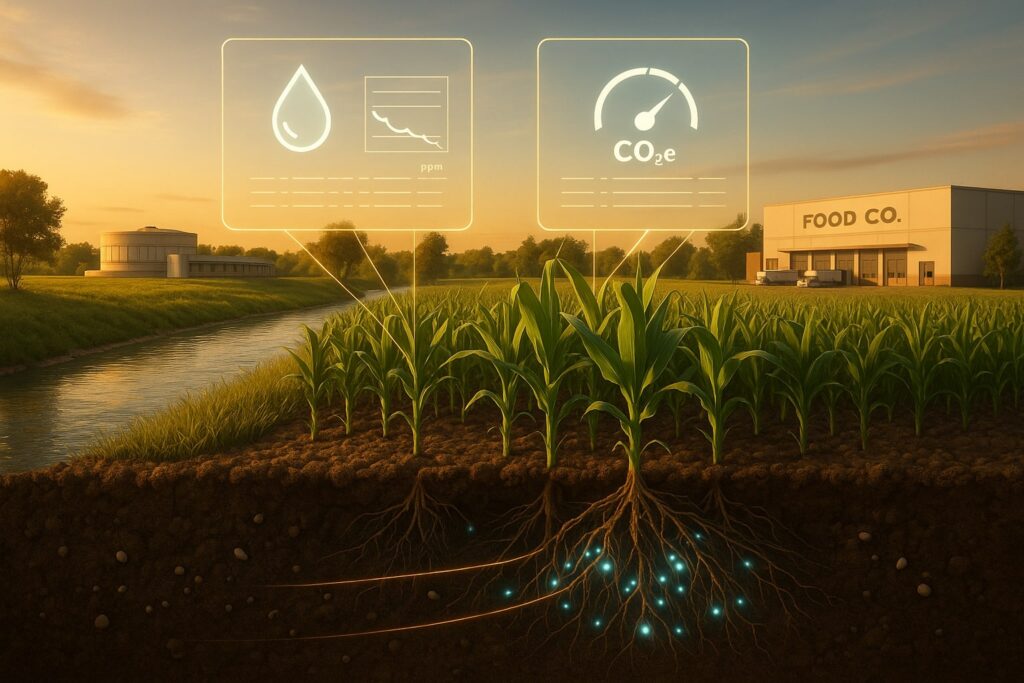

The immediate novelty is not the agronomy. Pivot Bio’s microbial products have been on U.S. fields for several seasons, offering a partial substitute for synthetic nitrogen by colonising roots and supplying ammonium through the growing cycle. SWOF has likewise paid farmers for verified environmental outcomes, chiefly improved water quality and associated greenhouse‑gas reductions. What is new is the explicit attempt to stack payments: to recognise that the same practice change—using a biological nitrogen source while optimising fertiliser rates—can generate two distinct outcomes financed by two distinct buyers. One buyer wants fewer nitrates in rivers; the other wants lower Scope 3 emissions in food and fuel supply chains.

If credible, the approach moves the conversation from virtue to margin. For growers, that could mean an uplift measured in tens of dollars per acre, while for corporate buyers and municipalities it offers a cheaper route to environmental compliance than building capacity or buying offsets of uncertain provenance. The devil, as ever, is in measurement and ledgers.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat has changed

The tie‑up links Pivot Bio’s nitrogen‑replacing microbes to SWOF’s outcomes‑based contracts. Farmers that replace a portion of urea, UAN or anhydrous ammonia with Pivot’s product will be eligible for SWOF payments tied to verified reductions in nutrient loss and greenhouse‑gas emissions. Crucially, the partnership is framed for supply‑chain reporting as much as for conservation, aligning with food majors’ Scope 3 targets and with the newly practical economics of clean‑fuel credits.

To date, most corporate insetting schemes have struggled to demonstrate that improvements on‑farm are additional, attributable and not already paid for elsewhere. Likewise, water‑quality trading programmes need a defensible method for estimating load reductions at the watershed level. The partnership is an attempt to operationalise both in one place—and to do so with farmer‑friendly cash flow.

The acre‑level maths

Payments from SWOF have averaged roughly $33–34 per acre in recent seasons, according to programme materials. Though rates vary by watershed and practice, in nitrate‑constrained counties municipal and utility buyers have sometimes funded higher payouts. SWOF typically advances a portion of the expected payment in season, with a true‑up after verification—useful for growers managing cash across a volatile input bill.

The input side of the ledger is familiar. If a farmer trims 30–40 lb of applied N per acre and substitutes Pivot’s microbes, the avoided synthetic nitrogen cost, priced at roughly $0.40–$0.60 per lb of N (region and timing matter), amounts to $12–$24 per acre. University and on‑farm trials cited by the company suggest neutral to slightly improved yields at those substitution rates.

Set against the friction of adopting a new product—additional scouting, record‑keeping, occasional sampling and agronomy time—say $5 per acre—the illustrative arithmetic is straightforward:

$33 SWOF payment + $18 input savings − $5 operating friction ≈ $46 per acre before any corporate premium attached to verified Scope 3 reductions.

No single farm is average, but in a margin business the difference between $10 and $40 of incremental value is the difference between a pilot and a programme. Moreover, if corporate supply‑chain buyers are prepared to underwrite multi‑year contracts, the stack begins to look like a funding mechanism for more durable practice changes: cover crops, reduced tillage, variable‑rate application—each with its own water and emissions profile.

Why stacking is controversial—and manageable

“Stacking” has become a byword for double‑counting. The concern is valid. If the same tonne of abatement is sold twice, either to two buyers or against two targets, the environmental ledger is distorted. But not all stacks are created equal, and regulation has been quietly evolving to distinguish between distinct outcomes marketed to distinct end‑uses.

Under U.S. water‑quality trading guidance, municipalities operating under NPDES permits may finance upstream nutrient reductions if doing so is more cost‑effective than plant upgrades. The environmental goal is compliance with local water standards; the accounting is hydrologic. By contrast, a food or fuel company’s Scope 3 accounting is governed by greenhouse‑gas protocols that—when properly applied—track emissions intensity changes in value chains, not fungible credits. Provided the claims are carefully ring‑fenced, the risks of double‑counting can be contained.

Three considerations matter in practice:

Different pollutants, different buyers. A city’s water utility “retires” the nitrate reduction against its regulatory obligations. A packaged‑food company books emissions‑intensity improvements in its supply chain under Scope 3 or agrifood guidance, in many cases as insetting rather than offsetting. The claims do not serve the same policy purpose.

Separate ledgers and serialisation. Water‑quality outcomes and greenhouse‑gas insetting should be tracked in separate registries or ledger systems, with transparent identifiers that make it clear what was measured, where and when. Where programmes remain private, audit provisions must be robust enough to satisfy regulators and external assurance providers.

Conservative baselines. For water, models calibrated to local soils and rainfall are standard; for emissions, baselines should reflect realistic nitrogen use and soil conditions, with nitrous‑oxide factors and embedded-fertiliser emissions documented at the method level. Over‑claiming is a reputational as well as an accounting risk.

A policy window is opening

The broader backdrop is helpful to this experiment. The Environmental Protection Agency continues to support water‑quality trading as a legitimate instrument under the Clean Water Act, and case studies have proliferated across the Midwest. At the same time, the Section 45Z clean‑fuel tax credit, in force for 2025–27, rewards lower lifecycle emissions in ethanol and biodiesel. That has prompted fuel blenders and large buyers to seek evidence of lower farm emissions in their feedstock catchment areas. Where measurement is credible, finance is now available to pay farmers for practice changes that deliver both cleaner water and lower emissions intensity.

Corporate climate programmes, once focused on certificate purchases, are gradually moving toward insetting—funding concrete changes within their own supplier base. For food majors with FLAG (Forest, Land and Agriculture) targets, nitrogen management is one of the cleaner levers: it is measurable, avoids land‑use accounting complexity and produces co‑benefits in water.

The technology and the MRV

Pivot Bio’s microbes are designed to colonise the rhizosphere and release plant‑available nitrogen through the season, reducing the need for a high upfront synthetic dose. The mechanism is not new, but the quality of the measurement matters. Reduced nitrate leaching and lower nitrous‑oxide emissions have been observed in trials when biological nitrogen replaces a portion of synthetic fertiliser and overall rates are optimised. SWOF layers on top a combined measurement, reporting and verification (MRV) framework: field‑level practice data, modelled outcomes and, in some cases, sampling to validate estimates. Payments are contingent on verification.

The two systems intersect at the farm gate. The more granular the data—on soils, weather, timing and rates—the stronger the claims, and the easier it is for both a water buyer and a corporate supply‑chain buyer to justify their expenditure to auditors and, ultimately, to the public or to shareholders.

Who gains, who loses

The potential winners are easy to spot. Farmers in nitrate‑sensitive watersheds gain a new revenue stream and a reason to experiment with lower synthetic rates. Water utilities gain a cheaper route to compliance than steel‑and‑concrete upgrades. Food and fuel companies gain a defensible way to show progress on Scope 3 that is tied to real practices rather than certificates.

The risks sit with participants that cannot demonstrate additionality or durability—and with incumbent fertiliser suppliers in regions where verified 30–40 lb‑per‑acre reductions become the norm. The latter is not an existential threat to nitrogen markets, but in local geographies it would be felt. A secondary risk is reputational: if programmes over‑claim or paperwork is sloppy, the backlash will be swift, and future stacks will be harder to sell.

What to watch in the next 6–12 months

Contract structure. The first joint contracts will be instructive. Look for language that makes the non‑fungibility of claims explicit—water outcomes retired for regulatory compliance, supply‑chain emissions reductions accounted for as insetting—and for provisions that survive changes in corporate climate standards.

Payment levels. If average payouts rise above $40 per acre in hotspots where nitrate caps bite and municipal demand is strong, adoption could inflect. Price levels will also be a proxy for how confident buyers are in MRV.

Audit trails. The best early signal will be the language that appears in corporate sustainability reports and utility board papers this winter. If buyers are willing to disclose methods and verification partners, this will move faster.

Interaction with 45Z. Biofuel buyers have new reasons to pay for farm‑level emissions improvements. Watch for offtake‑style agreements that bundle feedstock supply from low‑emissions acres with premiums tied to MRV.

How to underwrite the opportunity (investor lens)

Until there is multi‑season field data at scale, sensible investors will underwrite conservatively. That means assuming:

- Round‑trip scrutiny: third‑party checks on both the water and emissions components; no reliance on unverifiable certificates.

- Moderate yields‑at‑risk: neutral rather than improved yields until local data demonstrate otherwise.

- OPEX savings: explicitly valuing the reduced fertiliser bill; not over‑estimating operational friction on data collection.

- No resale of credits: insetting only on the corporate side; no attempt to claim the same reductions in voluntary carbon markets where rules would prohibit it.

The prize is not small. If stacking is accepted by regulators and auditors, per‑acre economics improve enough to matter in the P&L of large row‑crop operations. For Pivot Bio and its peers, it would validate a route to mainstream adoption that does not rely on commodity price spikes. For SWOF and similar programmes, it would move outcome‑based conservation from a line item in a grant budget to a service model with multiple durable buyers.

The bigger picture

American farm policy has spent decades subsidising practices that improve water quality and soil health. Corporate climate programmes have, for their part, struggled to convert money into measurable change on real acres. The most promising feature of the Pivot Bio–SWOF experiment is that it treats farmers as suppliers of verifiable environmental services, rather than as recipients of one‑off incentives. If the ledgers are kept clean and the measurement survives scrutiny, the same acre may soon be paid—fairly and transparently—by two customers for two different things it delivers well: cleaner water and lower emissions intensity.

The marketplace has been waiting for such a proof point. Now it needs to see the contracts.